Welcome to 2023! I’m determined to publish at least one article a week here. I thought I’d kick this off with something easy: the problems raised by online speech. Would love your thoughts on my problem statement below: What did I miss? What did I understate or overemphasize? Most of all, if you have proposed solutions, let’s talk!

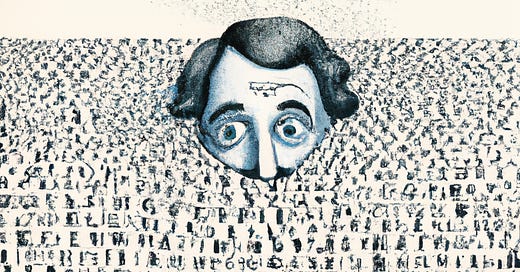

The internet and especially social media platforms have broken barriers that were holding back billions of people from connecting with others. The resulting swarm of new connections and communications has huge benefits but has also caused real problems, including disrupting and angering powerful incumbents. Yet many of the proposed regulatory and business model fixes to these problems would rely on centralized gatekeepers, diminishing the greatest benefits of social media to individuals.

The ability of a concentrated few to shape society’s speech environment has waxed and waned throughout history. In the fifteenth century, the printing press exploded the slipping elite control over ideas, leading to revolution, conflict -- and an unprecedented, sustained increase in living standards. More recently, the gatekeeper roles of powerful publishers and broadcasters has diminished in the eruption of communications facilitated by internet platforms. As a result, the average person today possesses an ability and freedom to speak to a broad audience that is unparalleled in human history.

A mere decade ago, these internet technologies were perceived by many elites to be avenues for spreading democracy and liberating the oppressed.1 Today, the elite consensus – across bipartisan lines – focuses on the risks that such technologies pose for incumbent institutions, including democracy itself. This shift in perception is profound: compare the lauding of such technologies during the Arab Spring with the criticisms and blame they face for the events of January 6, 2021.

The cause of this shift is straightforward. These technologies have disrupted existing institutions across the board, especially media and political power centers. The clearest disruption has been the complete overturning of the traditional advertising-funded content production business models of older media, especially print media.2 Furthermore, those who seek power always seek to control the flow of information in society, but this was easier to do when there were fewer gatekeepers; the internet made political control of information more difficult.

That displaced and threatened elites have a strong incentive to criticize these new models of communication does not mean all their criticisms are unwarranted. The tremendous freedom provided to individuals by social media can and has been abused. Individuals can be terrible to each other online. And these platforms enable rapid formation of persistent crowds, which can become mobs when stirred up.3 Polarized, passionate, and organized groups – usually mapping to political extremes -- dominate online conversations. As Renee DiRasta has said,

“The silent, moderate majority seems likely to be rendered even more silent, as it’s flanked by persistent digital crowds on both sides. It will either have to discover some passionate fervor and form its own activist crowd, or it will need to influence the structure and design of technology itself.”4

The formation of crowds online has many interesting implications, and society is still adapting. In the meantime, people have harmed others using social media.

Thus, platforms face market, political, and societal pressure to control the speech on their services. People across the political spectrum accuse platforms of fostering hate, censoring speech, and harming journalism – although they define those terms very differently. But regardless of what outcomes critics seek, nearly all of them advocate for the platforms controlling the speech that flows through their services. The platforms themselves have exacerbated the problem by touting their own ability to sufficiently govern user content.

This centralized approach to addressing the concerns of social media, if pursued, will eliminate many of the technology’s benefits.

There is no one social template for the process of knowledge production. Knowledge is produced through an iterative, emergent process of interaction among different ideas, testing them against each other and against reality. This iteration can happen on the level of individual ideas, but it also happens at multiple higher levels, within the institutions that are used in the production and communication of ideas. In short, society has developed institutions (such as newsrooms and universities) and norms (such as journalism ethics and good manners) that shape its knowledge production process. There is much useful and important embedded knowledge in these institutions and norms, including in the incumbent institutions that are under threat from social media.

Social media companies and users are also developing institutions and norms. The biggest platforms have invested millions of dollars in staff and development of complex procedures to govern the speech content on their platforms. Users also continue to develop norms in accordance with the incentives and affordances provided them by the platforms they use.

Unfortunately, both the platforms and their critics take a largely centralized view of the knowledge development process, believing that there is some single (or small) set of designed criteria for social media tools that will eliminate harms and retain benefits. Such centralization may indeed increase elite control over media, but as such would diminish the benefits to individuals and to the overall production of knowledge. It could also enable enormous abuses of power. (See, e.g., Chinese government manipulation of social media content.)

We need alternative, politically feasible policy and business approaches that support the continued evolution of institutions and norms to better support a more pluralistic, classically liberal society where ideas are debated while individuals are treated with dignity.

https://www.politico.com/story/2015/08/hillary-clinton-2016-internet-freedom-121229 (discussing Secretary Clinton’s Internet Freedom Agenda, and noting that “she seized on the fact that the online world was fast becoming an important organizing platform for traditionally dispossessed people, including women, democracy activists, civil society groups and gay and transgender people.”)

Ramsi Woodcock, When Writers are a Special Interest: The Press and the Movement to Break Up Big Tech, https://zephyranth.pw/2019/07/15/when-writers-are-a-special-interest-the-press-and-the-movement-to-break-up-big-tech/

Renee DiRasta, Crowds and Technology, https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2016/09/15/crowds-and-technology/

Id.